Tags : #WesternSahara #Morocco #Polisario #UNO #MINURSO #ChristopherRoss #KimBolduc #DGED #Lobbying #diplomacy #HackerChrisColeman

By Ignacio Cembrero

For two months, a fake profile has been posting the kingdom’s secrets online via Twitter. The government and political parties dare neither to analyze nor debate the consequences of the hacking of thousands of Moroccan diplomatic cables.

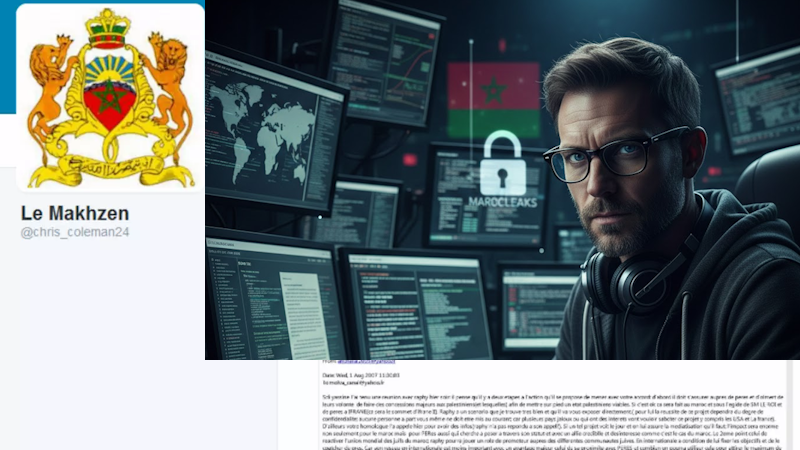

On the surface, he doesn’t seem very professional, yet he has managed to turn the authorities of the country reputed to be the most stable in North Africa upside down: Morocco. Since October 2, an anonymous profile (@chris_coleman24) has been distilling hundreds of cables from Moroccan diplomacy, the General Directorate for Studies and Documentation (DGED)—the Moroccan equivalent of the American CIA or the French DGSE—and also emails from seemingly close-knit press figures. He has even posted private photos online, such as those from the wedding of the Minister Delegate to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mbarka Bouaida, which are of little interest.

All of this is dumped onto the network in total disarray—some documents are even uploaded three times—and in diverse formats. The person posing as Chris Coleman, the coach of the Welsh national football team, began his disclosures on Facebook. His page was shut down. He then migrated to Twitter, but his account suffered the same fate until he managed to convince the company to reopen it.

His tweets linked to documents uploaded to file storage and sharing sites like Dropbox, Mediafire, or 4Shared, but his accounts on these platforms were closed. « It is true that for several days, the Makhzen has increased its threats to discourage me, » he complained on Twitter. « It has mobilized significant resources, particularly financial ones, to prevent the dissemination of information, » he added, while promising to continue fighting at the risk of his life. The metadata accompanying his tweets suggests he is in Morocco, but he may have managed the feat of deceiving Twitter about his location.

A State at Odds with the United Nations

This game of cat and mouse demonstrates the extent to which the person behind this anonymous profile is, in appearance, the polar opposite of the professionalism of Julian Assange—the man who defied the United States in 2010 by disclosing 250,000 U.S. State Department telegrams with the collaboration of four major media outlets.

In one of his rare comments, « Chris Coleman, » who displays sympathies for Sahrawi independence, explained that his goal was to « destabilize Morocco. » He certainly did not succeed in doing so, but despite his amateurism on social networks, he has shaken the Makhzen.

The quality of the material posted online has something to do with it. One discovers a Moroccan state angry with the United Nations Secretariat, and whose relations are also strained with the U.S. State Department. For example, since May 2014, Morocco has refused to allow Canadian Kim Bolduc to take office in El Aaiun, after she was appointed head of the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO), the UN contingent deployed in this former Spanish colony.

Rabat also constantly puts spokes in the wheels of the mission of American Christopher Ross, the personal envoy of UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon to the Sahara—a mediator sensitive to human rights and fundamentally in favor of granting autonomy to this territory to resolve the conflict. In a cable from Omar Hilale, then Moroccan ambassador to the UN in Geneva, he is described as an alcoholic who has become clumsy with age (he is 71), unable even to put on his jacket by himself.

The highlight of the revelations is undoubtedly the secret verbal agreement concluded in November 2013 at the White House between President Barack Obama and King Mohammed VI. The United States renounced—as they had done in April of that year—asking the Security Council to expand MINURSO’s mandate to include human rights, but obtained three concessions in exchange. First, Morocco would stop trying civilians in military courts; second, it would facilitate visits to the Sahara by officials from the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights; and third, it would legalize independent Sahrawi associations, such as the Sahrawi Collective of Human Rights Defenders (CODESA) led by activist Aminatou Haidar. On this last point, the promise has not yet been kept.

While Morocco’s relations are rather poor with the UN Secretariat, they are, conversely, much better with two UN bodies: the High Commissioner for Human Rights and the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), both in Geneva. Moroccan diplomacy has known how to make friends among high-ranking officials who inform them of their opponents’ initiatives and even help them abort or distort their projects. An example is the nearly clandestine stay in Geneva in 2012 of Mohamed Abdelaziz, the leader of the Polisario Front and president of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic.

As for DGED agents and their collaborators, they manage—through financial means—to get French, American, and even Italian journalists and think tanks to produce articles and analyses favorable to Moroccan views and detrimental to Algeria and the Polisario Front, which has claimed the independence of Western Sahara since 1973. The DGED also works through intermediaries to seduce the Jewish lobby in the United States, hoping it will influence the Obama administration to be more sympathetic toward Moroccan views on the Sahara. We also learn that Israel and Morocco maintained a permanent political dialogue, at least in 2011 and 2012.

Ultimately, the reading of hundreds of cables shows a Moroccan diplomacy that views the world through the lens of the Sahara. This piece of desert is everywhere: in Association Council meetings with the European Union, in ministerial visits to Europe, and in relations with countries as far away as Paraguay. This Saharan « monomania » means that Morocco takes little interest in other global debates. It only gets involved if it can derive a benefit for what Moroccan diplomats call the « national question. »

No Official Reaction

Chris Coleman and his tweets have been in every hallway conversation in the Rabat Parliament, in the cafes frequented by high-ranking officials, and at diplomatic cocktails in recent weeks. However, there has been no public explanation from the government regarding this breach in the communication system, nor about the investigation supposedly underway or its political consequences. The opposition has not deemed it useful to question the executive either.

The press, for the most part, has glossed over the affair, often echoing the thesis of Mbarka Bouaida, who believes that behind this fake profile are « pro-Polisario elements » acting with the support of Algeria. More than two months after the first leaks, Foreign Minister Salaheddine Mezouar in the Senate and government spokesperson Mustapha El-Khalfi before the press followed suit: « It is a frenzied campaign, orchestrated by adversaries, aimed at undermining Morocco, its image, and its power. »

This « ostrich policy » of a government and a political class that does not want to—or does not dare to—discuss this Moroccan-scale WikiLeaks also marks the difference with the United States. In late 2010, the U.S. investigated and spoke publicly about the repercussions of their massive disclosure for their foreign policy and image in the world. Morocco has not risked this exercise.

The Moroccan executive power is not confident enough: it feels too harassed over « its » Sahara to debate it in the public square. The few diplomatic setbacks it has suffered make it forget that the heavyweights of the international community, starting with the United States, wish for autonomy to be the solution granted to end a conflict that has lasted 39 years. They have been saying this for several years, as have the Élysée and successive governments of Spain, the former colonial power. Saharan independence, it is feared, would mean the destabilization of Morocco, which no one in Europe or America wants.

For the Moroccan autonomy offer to move forward, however, it must be credible. This means, above all, that Rabat must stop beating—or worse, imprisoning—those who advocate for the self-determination of the Sahara and take to the streets in Smara, Dakhla, or Laayoune to claim it.

This message warning of the harmful consequences of disproportionate repression is transmitted from time to time to the Moroccans by their Western interlocutors, starting with Christopher Ross, according to the cables consulted. It was even echoed half-heartedly in January 2014 by Driss El-Yazami, president of the National Human Rights Council created in 2011, during a discussion in Rabat on the implementation of the secret Washington agreement, according to a report of that meeting. But the message is not getting through. Rabat is turning a deaf ear.

IGNACIO CEMBRERO

- Note 1: The name of this account is « Le Makhzen, » which in colloquial Moroccan language refers to the State and its sovereign institutions.

- Note 2: See note 1.

- Note 3: SADR, the Republic proclaimed by the Polisario Front in 1976, recognized by the African Union but not by the UN.

Source : Orient XXI, DECEMBER 15, 2014